BIPOC & 2SLGBTQIA+ Youth: What They Need for ED Support in Alberta

By Kaci Switzer

Over the past four months, Silver Linings Foundation has been conducting a needs assessment to learn how we can make our services more inclusive. We started this project because research shows that equity-denied populations often struggle to access mental health and eating disorder support. The statistics are startling, including that 2SLGBTQIA+ youth who are Indigenous reported the highest rates of being diagnosed with an eating disorder (1). You can read more about the statistics that inspired this project in our October blog post: here.

We entered into this project with the main intention of striving to do better and learning directly from the community members that we serve. We connected with community organizations and conducted interviews with BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of colour) and 2SLGBTQIA+ (Two-Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and/or Questioning, Intersex, Asexual/Aromantic) youth. The following is a brief summary of our findings.

Youth Interviews

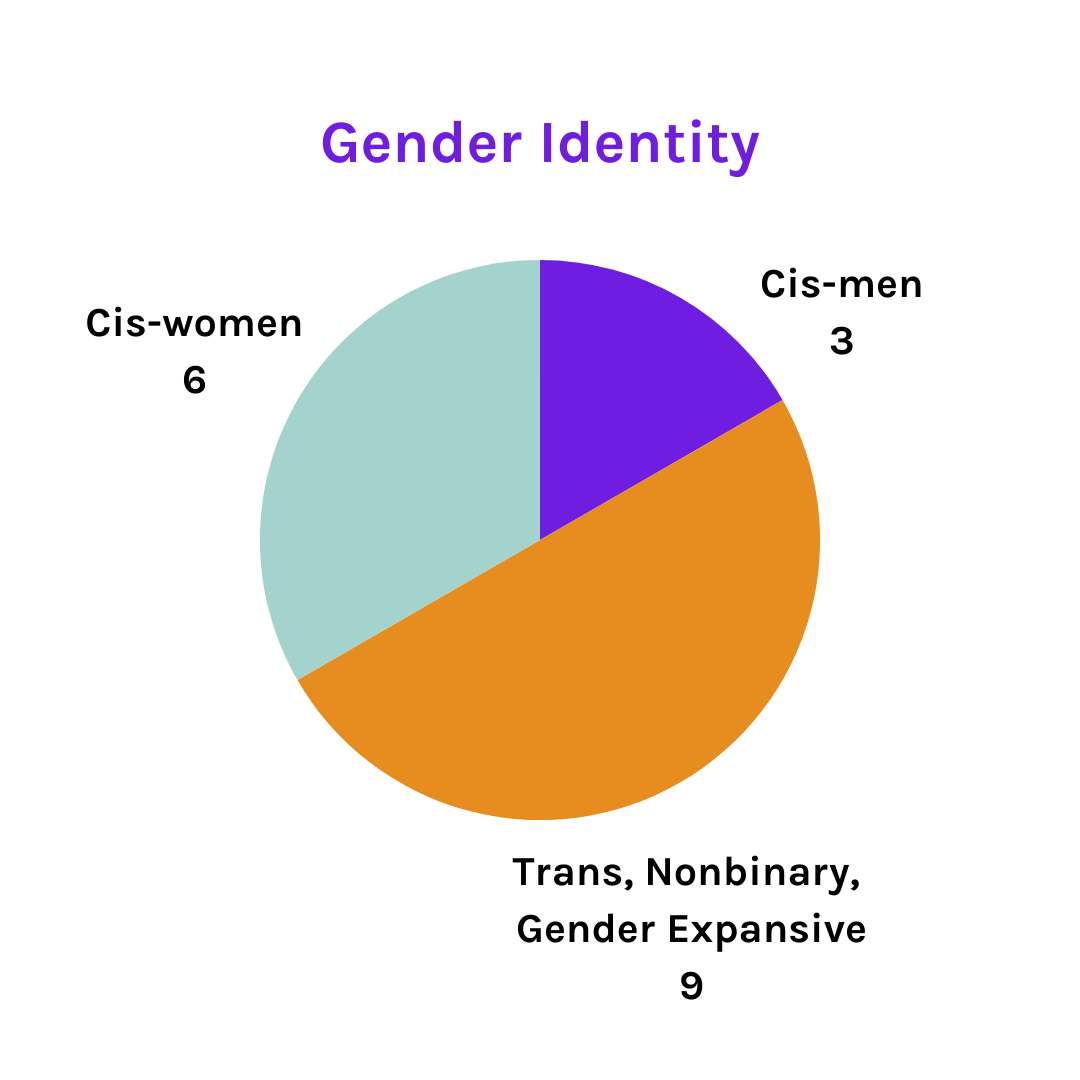

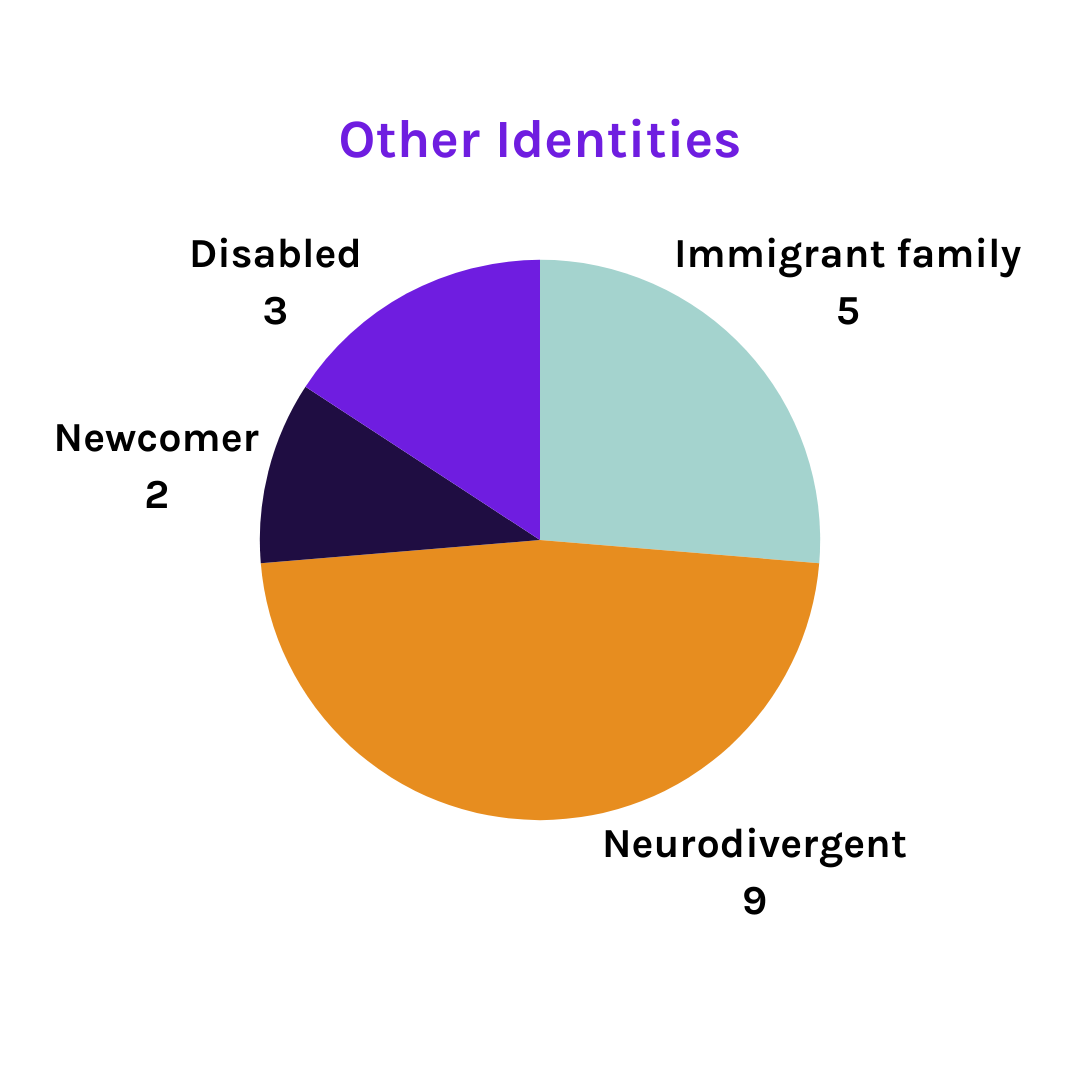

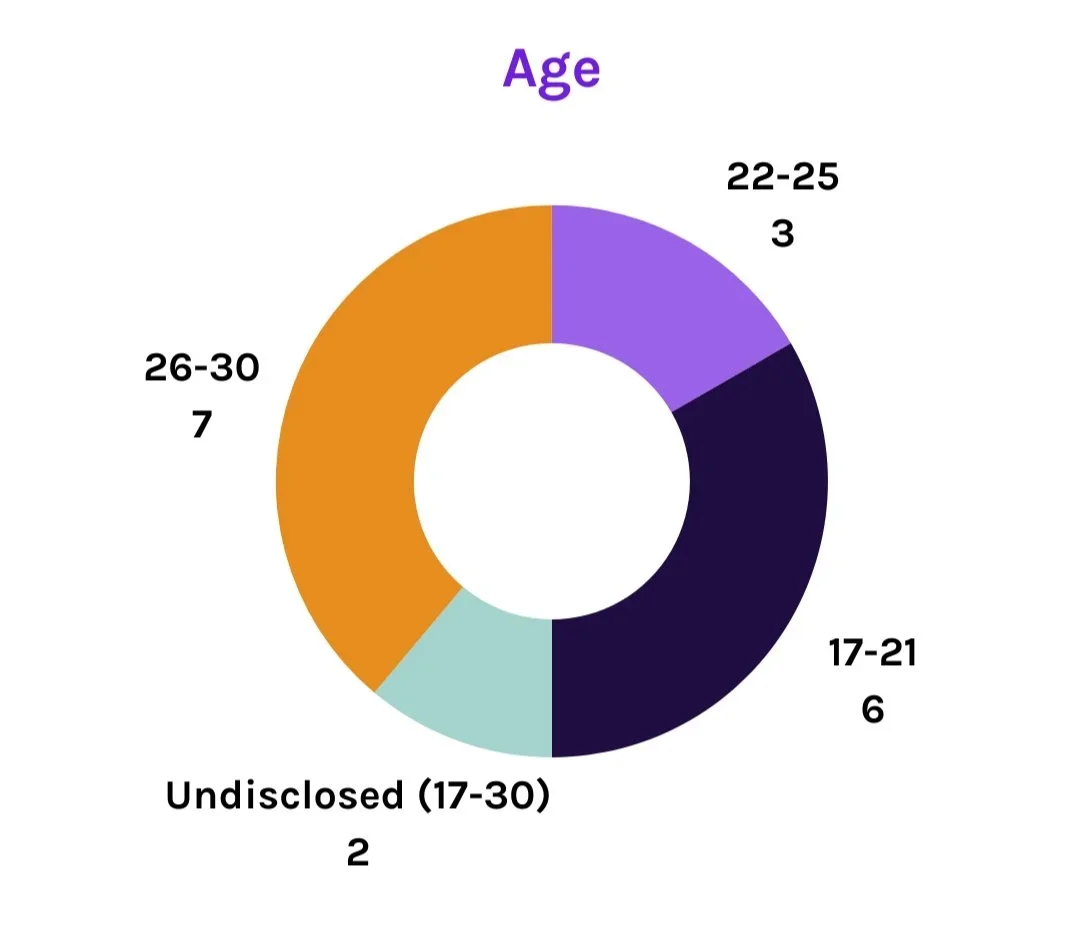

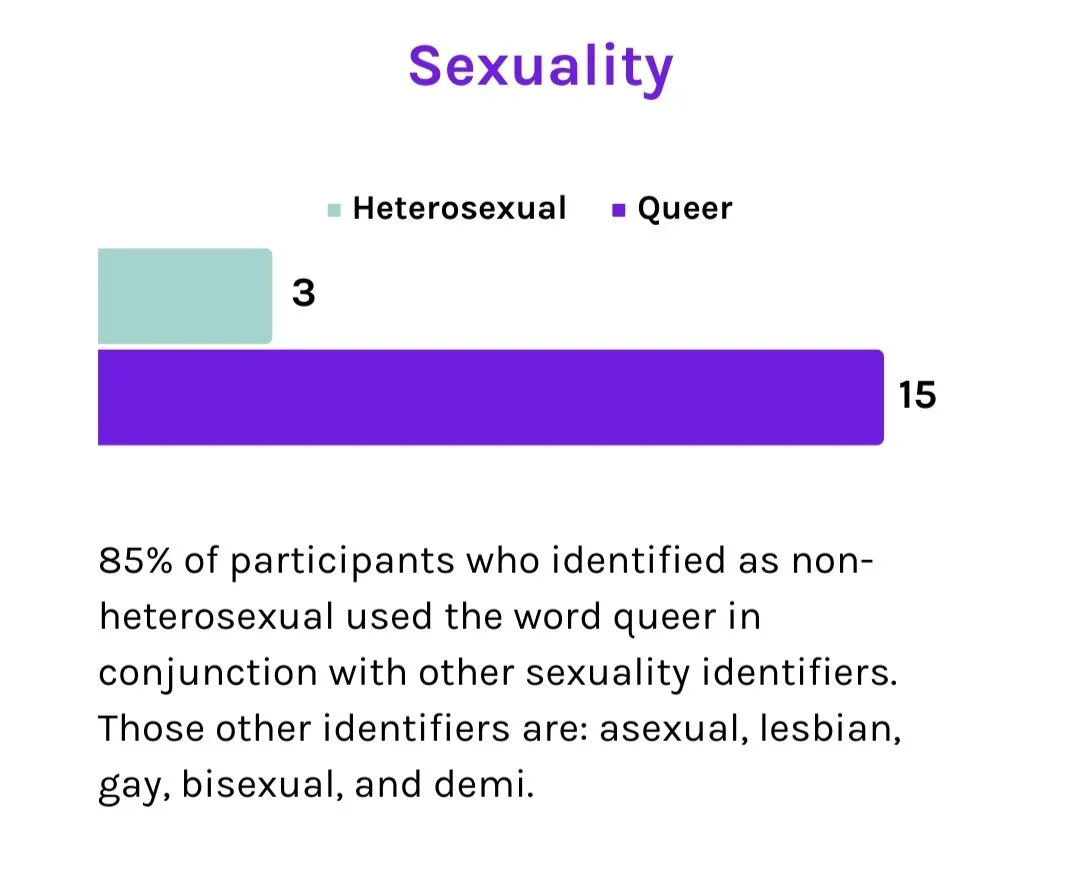

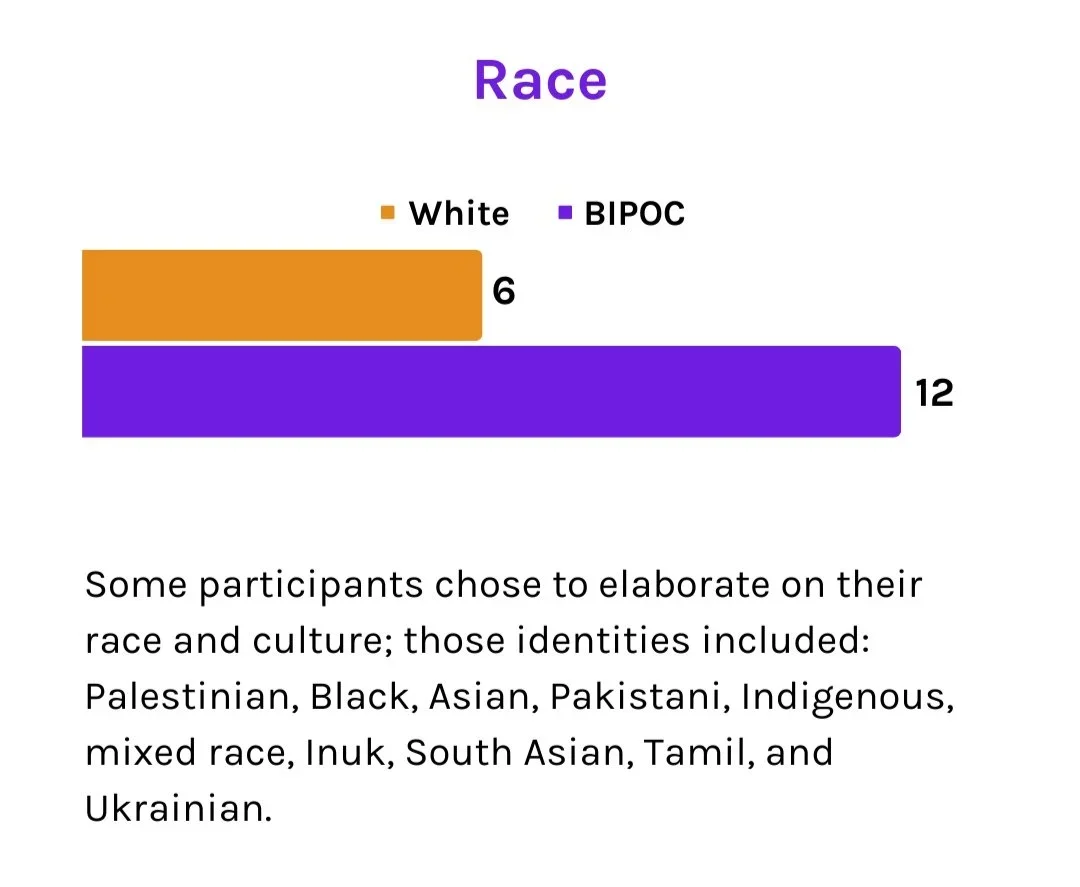

We conducted 18 interviews with youth who identified themselves as 2SLGBTQIA+ and/or BIPOC/racialized and were between the ages of 17 and 30. All participants were given the opportunity to self identify with their choice of words, including sharing any identities that they felt important to them and relevant to our conversation.

Before we dive in, it is important to note that all participants indicated that their desire to participate in this research was due to one or more of the following:

They had negative experiences with the mental health system

The lack of resources and knowledgeable practitioners available for BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ people

They want to make a positive impact on the way BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ people are treated within the mental health system

“When it comes to eating disorders, I haven't found anyone and because I don't fit the stereotypical look, I guess…they didn't think that I needed help. It wasn't something that they thought that I was going through so it was kind of brushed off.”

- Anonymous Participant, she/they,

mixed race, queer, neurodivergent

The interviews with youth focused on four areas: what barriers exist when seeking care, how to know an organization is inclusive, what types of resources and services are needed, and recommendations for change. Within each area, there were several themes and examples that arose in each area, with many of them overlapping significantly.

“There was definitely one particular time I can remember where somebody found out I'm Indigenous and there was an immediate change in tone. They were treating me like I was just here for drugs or something.”

- Anonymous Participant, they/he,

transmasculine, mixed Indigenous

Barriers to Seeking Care

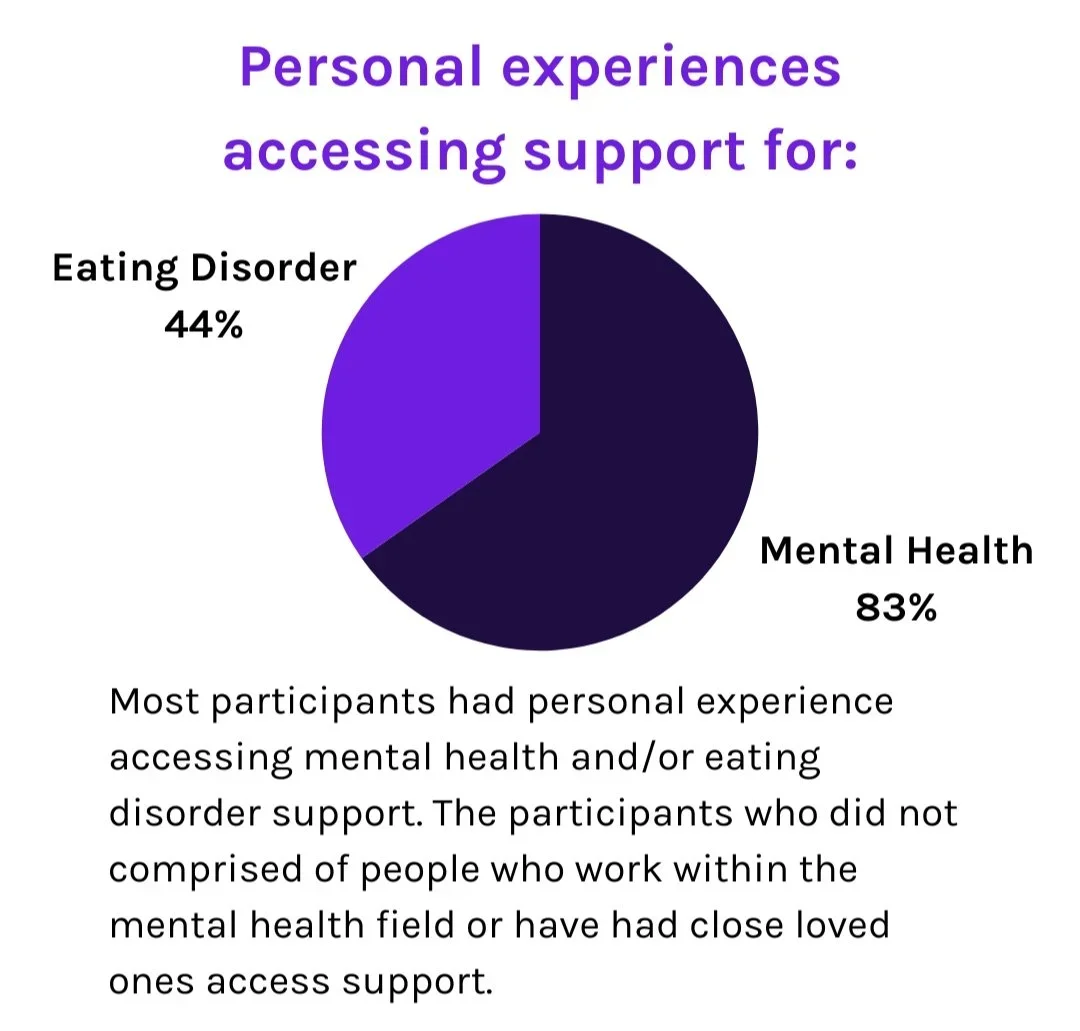

Participants were asked to share their personal experiences or understandings of barriers or challenges that BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ youth face when considering or actively accessing support services. Of the 16 participants who had experience seeking support for mental health and/or eating disorders, either through themself or a close loved one, 15 shared negative experiences with the process of accessing support and resources, communication with practitioners, and/or the continuity of care.

“There's such a long waitlist, that even though I have a practitioner…that I can access, I have to wait and it has been months. It has been [7] months.”

- B, they/them, queer,

trans/nonbinary, neurodivergent

KEY LEARNINGS:

Participants feel it is daunting and overwhelming to know where to begin and what to look for when seeking support, especially when care is urgently needed.

Most available resources or care providers are presented through a “white”, “Western”, “cishet (2)” lens.

Nearly all participants who indicated wait lists as a barrier identified as 2SLGBTQIA+

60% of participants stated financial cost

66% of participants expressed “fear” of discrimination, being denied care, or repercussions.

72% of participants indicated that “stigma”, “shame”, and “embarrassment” is one of the biggest barriers stopping people from getting help.

100% of participants stated that it is difficult to find providers who share their lived experiences or who understand the complexity of issues they face.

Desired Resources and Services

Participants were asked, what types of resources, supports, and services do they need and want to see available for anyone seeking help. Many participant answers were direct responses to the barriers they had previously identified.

“I feel like therapists, practitioners and providers should be more educated on common experiences of anti-fat bias that happen in the medical system.”

- Lauren, they/them, queer, nonbinary

AREAS OF IMPROVEMENT:

Eating disorder resources and practitioners that address the ways intersecting identities and experiences affect eating disorder presentation and recovery: fatness, neurodivergency, cultural stigma, queerness, gender expression, etc.

Support directly in communities and facilitated by people from within the community

Identity specific resources and programming: ex. support groups for people who are newcomers, trans, queer, or in bigger bodies.

Education should start young, include guardians of children, and be focused on destigmatizing mental health

Prevention and continuity of care: affordable, accessible, reduced waitlists, intercommunity collaboration, targets root causes, etc.

Inclusive Care

What indicators do you look for to know if an organization or practitioner is inclusive or will be safer for you to go? Participants shared a multitude of ways they protect themselves, these are only a few of their comments.

“It’s difficult to find therapists who are queer and also Arab. I think mentioning they have experience working with those populations is helpful.”

- Anonymous Participant,

he/him, Palestinian, gay

VISIBLE SIGNS TO LOOK FOR:

Visible rainbow or trans flags

Land acknowledgment

Health at every size (HAES)

Diversity of staff/practitioners and lived experience or clearly stated experience working with the community that the client belongs to

Inclusive language, imagery, and resources on website, social media, patient forms, and used within the space: inclusivity statement, pronouns, accurate disability terms, diverse experiences, client-centred language

Knowledgeable about systemic/root causes of oppression

Relevant, accurate, evidence-based resources

Evidence of training: cultural competency, anti-racism, 2SLGBTQIA+ identities and issues, Indigenous history, ableism, etc.

Testimonials from friends, family, or visible on the organization’s pages

Physical accessibility: ramps, chairs, sensory aware, gender neutral washrooms

Offers sliding scale, financial aid, or free consultations

“You can't wish yourself to be educated.

You have to go out and do the work.”

-Anonymous participant,

they/he, queer, trans, autistic

Moving Forward

KEY RECOMMENDATIONS FROM PARTICIPANTS:

Diversify both staff and programming

Engage with community members within their own communities

Collect and implement feedback from clients and stakeholders on a frequent and ongoing basis, especially equity-denied folks

Equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility training that specifically addresses issues and experiences of BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ people

Decolonize care through staff training, public land acknowledgment, Indigenous-specific programming, and giving back to Indigenous communities

Ensure physical and emotional accessibility of the space: ramp, seating, sensory awareness, trauma-informed, etc.

Increase visible inclusivity across digital platforms

Update digital resources and create a “how to access care” resource

In addition to seeking recommendations from youth, we met with three well established non-profit organizations in Calgary to learn from their experiences with serving BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ youth and begin to build lasting relationships between them and Silver Linings. The organizations we met with are: Centre for Sexuality, Action Dignity, and Calgary Outlink. They shared their expertise with us and invited us to think about the ways our organization can evolve.

KEY LEARNINGS FROM COMMUNITY ORGANIZATIONS:

Engagement and outreach must take place within the communities we want to serve, not from outside of them. This begins with building connections with community members and establishing trust.

Resources and services need to be informed by emerging issues and the unique needs of the communities we are serving.

We must learn about and attend to the systemic barriers that BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ people face, with specific attention given to intersectionality (3).

Asking for feedback from our clients and stakeholders on a regular basis is an important part of staying accountable to our community and ensuring we are meeting their needs.

“We start from the strength-based approach. We see that everybody has something to contribute and they are valued.”

- Action Dignity

Next Steps

We want to do better and this project was just one step in our process. Silver Linings is working diligently behind the scenes to implement recommendations from this project. Our next steps are in motion as we get ready to open our live-in treatment centre in Spring 2024 and we have begun the process of creating a “train the trainer” program for eating disorder practitioners.

Thank You!

This project would not be possible without the generous support of all our participants, our fellow non-profit organizations, and funding supplied by the Capacities Building and Emerging Issues Grant from the City of Calgary. Thank you to everyone who participated, your ideas are helping shape a better future for Albertans with mental health concerns and eating disorders.

REFERENCES

1. The Trevor Project. (2022). Research brief: Eating disorders among LGBTQ youth. https://www.thetrevorproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Embargoed_Feb-2022-Research-Brief.pdf

2. Cishet: common shorthand for cis-gender and heterosexual.

3. Intersectionality is a term coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 that describes the way race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, disability, and any other identity “intersect” or overlap to give or take away power from an individual. For example, a Black person experiences disadvantages and discrimination based on their race when compared to a white person. A Black person who is also gay will experience other forms of discrimination based on the intersection of their race and sexuality. To learn more about intersectionality, check out Crenshaw’s 2016 TED Talk, here: https://www.ted.com/talks/kimberle_crenshaw_the_urgency_of_intersectionality?language=en